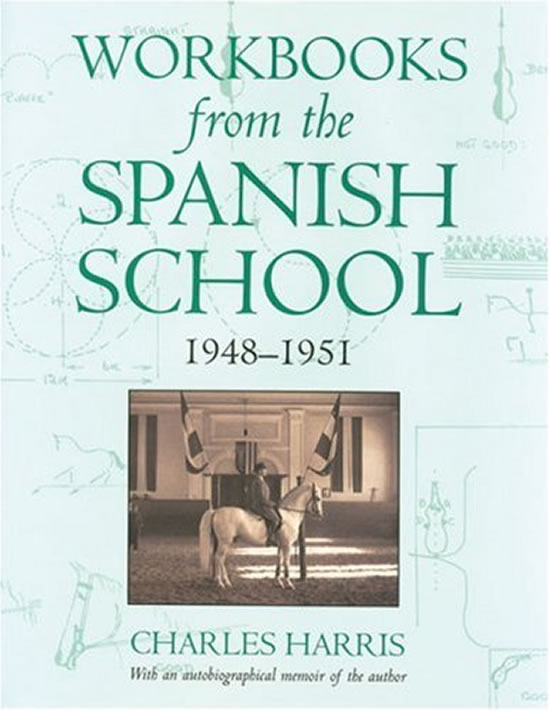

Charles Harris was the first and only pupil to complete the 1948-1951 course at the Spanish Riding School in Vienna. Every day he wrote down what he learned, illustrating each point and filling two thick notebooks.

These numbered notes are faithfully reproduced just as he wrote them, forming a unique record of classical horsemanship.

Reviews:

A wonderful companion volume for a rider’s library!, June 30, 2007

By Dr. Nancy L. Nicholson (Oxford, OHIO USA)

This book is beautifully produced and edited, with a fascinating collection of photographs. We owe much to Harris’ nephew Robert Sherman for understanding and for preserving valuable knowledge. As one of the other reviewers points out, it is an outstanding volume for one’s own library or as a gift. But let me indicate exactly why this is the case.

1a) This volume is an important technical work in its own right. Its drawings are in the order from Harris’ notebooks and not a rider’s “curriculum,” so the savvy reader might make a custom index for items of specific interest. The Spanish School notes are wide-ranging, from exercises basic to riding a green horse to setting up a flying change (don’t try this one without a truly supple horse that can execute a flawless passade – not passage! – in canter – see Sections 23, 32 & 53). One updated answer you can take into the technical portion of the book is the reason for the importance of tempo (strides per minute), as this was one issue that Mr. Harris did not fully resolve in 1948-51. An examination of frames of equine gaits plus data from dressage gaits shows that dressage horses use only a fraction of the gaits and tempos available to horses, and these are in the slower range of strides per minute. Milton Hildebrand’s article on this is in the journal Science (1965), forming one important pillar of understanding the relation of tempo to dressage gaits. The rhythm (order and timing of leg motions within walk, trot, canter) in those slower tempos is what enables the transitions between the dressage gaits. Dressage transitions, which are the most frequently ridden movement in dressage, must be fluent, level, prompt. Hasty or quick tempos exclude them from the needed step order in a stride, precisely because the legs in the start gait must be shifted to the new pattern in the end gait: and this requires nearly two seconds – much more demanding of ground contact time (aerobic demands on big muscles!) than just scooting from one gait to the next. So dressage transitions are completely dependent on tempo. Curiously, very little has been published on dressage transitions BioMechanical Riding and Dressage: A Rider’s Atlas, and this volume has that problem. However, its discussion of passage/piaffe transitions is very clear on the aids for that High School movement.

1b) Harris’ notes are focused on correct position of the rider, the position that unifies rider and horse, enabling clear communication between partners. Look carefully at Harris’ diagrams for the aids, because they form an unambiguous set of motions for safe, balanced riding.

2) Biographical material is relevant not only to the personal and intellectual development of Riding Master Charles Harris, but offers historical windows into the general social order of the Continent and of England in the 20th century. The transfer of true knowledge (in the scientific sense of verifiable, repeatable and data-dependent) is at the mercy of personality conflicts and of institutional inflexibility. Thus Francois Robichon de la Gueriniere’s observation more than two centuries ago about the lack of truly fine riders. This multifaceted problem persists in our era and a portion of it is nicely chronicled in this book.

3) Charles Harris’ recollections are outstanding and straightforward, especially refreshing in an era of twaddle, pop-psych advice about riding and general departure from biomechanically correct classical equitation (by this I mean equitation in general, not only dressage). A couple of brief examples should whet your appetite for the whole repast of this volume. On what to eat before a longe session (Section 54): “Diet is important for earnest riders . . . avoid eating anything fatty or greasy until after you finish the lesson.” Toast/bread and jam illustrated. And from the biographical section pages (38-9) comes the reason for the Classical Seat (survival through balance). “. . . that holiday in Switzerland. They had a festival . . . a kind of pre-hunting festival where they all go crackers on horses between two points fifteen or twenty miles apart. [?Hubertusjagd] I get on the horse and the Swiss officers (on theirs) and off we start. Now the first thing I see is a bloody drop of about eight foot in front of me, a little stream. I thought ‘Bloody ____, what’s this? We’ve gone off on a bloody split _____ gallop. . . . I can do this. . . . I’m on a horse. I’m in control. I’m not doing anything.’ Some of the riders are tumbling off, some are hanging round their horses’ necks. Some horses are falling . . . I just sit there like the Duke of Rhubarb.” Harris attributes his survival of this potentially lethal four hour adventure correctly to his year on the longe at the Spanish School learning to balance without stirrups or reins. Get the book, as there are even niftier accounts on its pages! And there is enough information in his notes so, if you are a kinesthetically aware person, you just might be able to ride like the Duke (or Duchess) of Rhubarb.

4) It is a companion volume to these other outstanding works:

Because Charles Harris roomed with Spanish School Director Aloys Podhajsky in exchange for giving lessons in English, Podhajsky’s plus his will provide additional pleasant years of reading. The Spanish School is, in its turn, is historically inspired by the masterwork by Francois Robichon De La Gueriniere translated by Tracy Boucher (you can also find this in the original French). Finally, centuries of safe riding are aptly founded on Dom Duarte’s 15th century masterpiece the or “How to ride well in any saddle” (the answer: a calm, alert mental state needed for any rider to be safe). This jewel of horsemanship has been issued in English under the title by Antonio Franco Preto and Steven Muhlberger. These books will give you a hint of a unique art passed forward through centuries in the companionship and touch between two species.

OK, you may be spending serious money on these volumes (all available on Amazon), but they are classics in the formal sense of durable knowledge. Eat your toast and jam and ride with joy.

For The Serious Classical Dressage Trainer, December 8, 2006

By Patricia M. Ross “Foxwin Morgans” (Elmira, NY USA)

This book is not an easy read, especially the biography chapters, but contains a wealth of information when used as intended, as a daily workbook. Open to any page in the “workbook” chapters, and you will find something of value.

A Book Every Rider Should have!!!, October 26, 2005

By Cecilia Gutierrez

It is an excellent reference book, the drawings show the movements very well, all riders should have it and use it. It is a delight to read!

I have already bought six of them and given them away as presents, to colleagues, students and friends.

You will not be dissapointed, I am sure of that!

About the Author:

Charles Harris was a student of the Spanish Riding School.

5.0 out of 5 stars

wonderful book- but why does the price vary so violently?

I lusted after this book after looking at a friend’s copy. Such a personal account and training information from the Spanish Riding School.

I LOVE IT!

Hi Xenos,

I think the price is up and down so much because the print run was so small and sold out quickly. Typical supply and demand market conditions. This is a very rare read indeed!

5.0 out of 5 stars

Required reading.

If you are a dressage trainer or instructor this book is required reading to consider yourself educated in dressage.